Four Times Of The Day on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Four Times of the Day'' is a series of four oil paintings by English artist

''Four Times of the Day'' is a series of four oil paintings by English artist

Hogarth designed the series for an original commission by

Hogarth designed the series for an original commission by

A trail of peculiar footprints shows the path trodden by the woman on her

A trail of peculiar footprints shows the path trodden by the woman on her

The composition of the scene juxtaposes the prim and proper Huguenot man and his immaculately dressed wife and son with these three, as they form their own "family group" across the other side of the gutter. The head of

The composition of the scene juxtaposes the prim and proper Huguenot man and his immaculately dressed wife and son with these three, as they form their own "family group" across the other side of the gutter. The head of

''Morning''

at National Trust Collections

''Night''

at National Trust Collections

"William Hogarth - Four Times of the Day", La Clé des Langues (English)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Four Times Of The Day 1736 paintings Painting series Paintings by William Hogarth Paintings in the West Midlands Paintings in the East Midlands

''Four Times of the Day'' is a series of four oil paintings by English artist

''Four Times of the Day'' is a series of four oil paintings by English artist William Hogarth

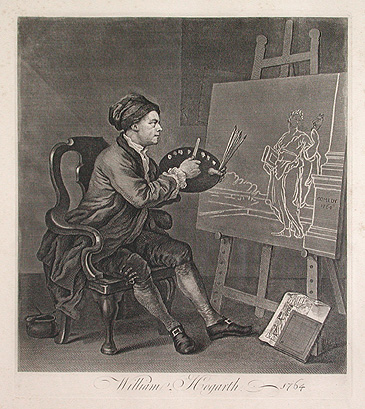

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like s ...

. They were completed in 1736 and in 1738 were reproduced and published as a series of four engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a Burin (engraving), burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or Glass engraving, glass ...

s. They are humorous depictions of life in the streets of London, the vagaries of fashion, and the interactions between the rich and poor. Unlike many of Hogarth's other series, such as ''A Harlot's Progress

''A Harlot's Progress'' (also known as ''The Harlot's Progress'') is a series of six paintings (1731, now destroyed) and engravings (1732) by the English artist William Hogarth. The series shows the story of a young woman, M. (Moll or Mary) H ...

'', ''A Rake's Progress

''A Rake's Progress'' (or ''The Rake's Progress'') is a series of eight paintings by 18th-century English artist William Hogarth. The canvases were produced in 1732–1734, then engraved in 1734 and published in print form in 1735. The series ...

'', ''Industry and Idleness

''Industry and Idleness'' is the title of a series of 12 plot-linked engravings created by William Hogarth in 1747, intending to illustrate to working children the possible rewards of hard work and diligent application and the sure disasters at ...

'', and ''The Four Stages of Cruelty

''The Four Stages of Cruelty'' is a series of four printed engravings published by English artist William Hogarth in 1751. Each print depicts a different stage in the life of the fictional Tom Nero.

Beginning with the torture of a dog as a ch ...

'', it does not depict the story of an individual, but instead focuses on the society of the city in a humorous manner. Hogarth does not offer a judgment on whether the rich or poor are more deserving of the viewer's sympathies. In each scene, while the upper and middle classes tend to provide the focus, there are fewer moral comparisons than seen in some of his other works. Their dimensions are about by each.

The four pictures depict scenes of daily life in various locations in London as the day progresses. ''Morning'' shows a prudish spinster making her way to church in Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

past the revellers of the previous night; ''Noon'' shows two cultures on opposite sides of the street in St Giles

Saint Giles (, la, Aegidius, french: Gilles), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 6th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly lege ...

; ''Evening'' depicts a dye

A dye is a colored substance that chemically bonds to the substrate to which it is being applied. This distinguishes dyes from pigments which do not chemically bind to the material they color. Dye is generally applied in an aqueous solution an ...

r's family returning hot and bothered from a trip to Sadler's Wells

Sadler's Wells Theatre is a performing arts venue in Clerkenwell, London, England located on Rosebery Avenue next to New River Head. The present-day theatre is the sixth on the site since 1683. It consists of two performance spaces: a 1,500-sea ...

; and ''Night'' shows disreputable goings-on around a drunken freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

staggering home near Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City; ...

.

Background

''Four Times of the Day'' was the first set of prints that Hogarth published after his two great successes, ''A Harlot's Progress'' (1732) and ''A Rake's Progress'' (1735). It was among the first of his prints to be published after theEngraving Copyright Act 1734

The Engraving Copyright Act 1734 or Engravers' Copyright Act (8 Geo.2 c.13) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain first read on 4 March 1734/35 and eventually passed on 25 June 1735 to give protections to producers of engravings. It is al ...

(which Hogarth had helped push through Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

); ''A Rake's Progress'' had taken early advantage of the protection afforded by the new law. Unlike ''Harlot'' and ''Rake'', the four prints in ''Times of the Day'' do not form a consecutive narrative, and none of the characters appears in more than one scene. Hogarth conceived of the series as "representing in a humorous manner, morning, noon, evening and night".

Hogarth took his inspiration for the series from the classical satires of Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

and Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the ''Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

, via their Augustan counterparts, particularly John Gay

John Gay (30 June 1685 – 4 December 1732) was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for ''The Beggar's Opera'' (1728), a ballad opera. The characters, including Captain Macheath and Polly Peac ...

's ''Trivia

Trivia is information and data that are considered to be of little value. It can be contrasted with general knowledge and common sense.

Latin Etymology

The ancient Romans used the word ''triviae'' to describe where one road split or forked ...

'' and Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

's " A Description of a City Shower" and "A Description of the Morning

"A Description of the Morning" is a poem by Anglo-Irish poet Jonathan Swift, written in 1709. The poem discusses contemporary topics, including the social state of London at the time of the writing, as well as the developing of commerce and busines ...

".Paulson (1992) pp.140–149 He took his artistic models from other series of the "Times of Day", "The Seasons" and "Ages of Man", such as those by Nicolas Poussin

Nicolas Poussin (, , ; June 1594 – 19 November 1665) was the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style, although he spent most of his working life in Rome. Most of his works were on religious and mythological subjects painted for a ...

and Nicolas Lancret

Nicolas Lancret (22 January 1690 – 14 September 1743) was a French painter. Born in Paris, he was a brilliant depicter of light comedy which reflected the tastes and manners of French society during the regency of the Duke of Orleans and, late ...

, and from pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

scenes, but executed them with a twist by transferring them to the city. He also drew on the Flemish "Times of Day" style known as ''points du jour

Point or points may refer to:

Places

* Point, Lewis, a peninsula in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland

* Point, Texas, a city in Rains County, Texas, United States

* Point, the NE tip and a ferry terminal of Lismore, Inner Hebrides, Scotland

* Point ...

'', in which the gods floated above pastoral scenes of idealised shepherds and shepherdesses, but in Hogarth's works the gods were recast as his central characters: the churchgoing lady, a frosty Aurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

in ''Morning''; the pie-girl, a pretty London Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

in ''Noon''; the pregnant woman, a sweaty Diana in ''Evening''; and the freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, a drunken Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

in ''Night''.

Hogarth designed the series for an original commission by

Hogarth designed the series for an original commission by Jonathan Tyers

Jonathan Tyers (10 April 1702 – 1767) became the proprietor of New Spring Gardens, later known as Vauxhall Gardens, a popular pleasure garden in Kennington, London. Opened in 1661, it was situated on the south bank of the River Thames on ...

in 1736 in which he requested a number of paintings to decorate supper boxes at Vauxhall Gardens

Vauxhall Gardens is a public park in Kennington in the London Borough of Lambeth, England, on the south bank of the River Thames.

Originally known as New Spring Gardens, it is believed to have opened before the Restoration of 1660, being ...

.Paulson (1992) pp.127–128 Hogarth is believed to have suggested to Tyers that the supper boxes at Gardens be decorated with paintings as part of their refurbishment; among the works featured when the renovation was completed was Hogarth's picture of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key ...

. The originals of ''Four Times of the Day'' were sold to other collectors, but the scenes were reproduced at Vauxhall by Francis Hayman

Francis Hayman (1708 – 2 February 1776) was an English painter and illustrator who became one of the founding members of the Royal Academy in 1768, and later its first librarian.

Life and works

Born in Exeter, Devon, Hayman begun his arti ...

, and two of them, ''Evening'' and ''Night'', hung at the pleasure gardens until at least 1782.

The engravings are mirror images of the paintings (since the engraved plates are copied from the paintings the image is reversed when printed), which leads to problems ascertaining the times shown on the clocks in some of the scenes. The images are sometimes seen as parodies of middle class life in London at the time, but the moral judgements are not as harsh as in some of Hogarth's other works and the lower classes do not escape ridicule either. Often the theme is one of over-orderliness versus chaos. The four plates depict four times of day, but they also move through the seasons: ''Morning'' is set in winter, ''Noon'' in spring, and ''Evening'' in summer. However, ''Night''—sometimes misidentified as being in September—takes place on Oak Apple Day

Restoration Day, more commonly known as Oak Apple Day or Royal Oak Day, was an English, Welsh and Irish public holiday, observed annually on 29 May, to commemorate the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in May 1660. In some parts of England the ...

in May rather than in the autumn.

''Evening'' was engraved by Bernard Baron

Bernard Baron (1696? – 1762)

Web articl Library of Congress, lower section "About the Artists" was a French engraver and etcher who spent much of his life in England.

Life

Baron was born in Paris in 1696, the son of the engraver Laurent Baron ...

, a French engraver who was living in London, and, although the designs are Hogarth's it is not known whether he engraved any of the four plates himself. The prints, along with a fifth picture, ''Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn

''Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn'' is a painting from 1738 by British artist William Hogarth. It was reproduced as an engraving and issued with ''Four Times of the Day'' as a five print set in the same year. The painting depicts a compan ...

'' from 1738, were sold by subscription for one guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

(£ in ), half payable on ordering and half on delivery. After subscription the price rose to five shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

s per print (£ in ), making the five print set four shillings dearer overall. Although ''Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn'' was not directly connected to the other prints, it seems that Hogarth always envisaged selling the five prints together, adding the ''Strolling Actresses'' as a complementary theme just as he had added '' Southwark Fair'' to the subscription for ''The Rake's Progress''. Whereas the characters in ''Four Times'' play their roles without being conscious of acting, the company of ''Strolling Actresses'' are fully aware of the differences between the reality of their lives and the roles they are set to play. Representations of Aurora and Diana also appear in both.

Hogarth advertised the prints for sale in May 1737, again in January 1738, and finally announced the plates were ready on 26 April 1738. The paintings were sold individually at an auction on 25 January 1745, along with the original paintings for ''A Harlot's Progress'', ''A Rake's Progress'' and ''Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn''. Sir William Heathcote purchased ''Morning'' and ''Night'' for 20 guineas and ''£''20 6''s'' respectively (£ and £ in ), and the Duke of Ancaster

Earl of Lindsey is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1626 for the 14th Baron Willoughby de Eresby (see Baron Willoughby de Eresby for earlier history of the family). He was First Lord of the Admiralty from 1635 to 1636 and ...

bought ''Noon'' for ''£''38 17''s'' (£ in ) and ''Evening'' for ''£''39 18''s'' (£ in ). A further preliminary sketch for ''Morning'' with some differences to the final painting was sold in a later auction for ''£''21 (£ in ).

Series

Morning

In ''Morning'', a lady makes her way to church, shielding herself with her fan from the shocking view of two men pawing at the market girls. The scene is the west side of thepiazza

A town square (or square, plaza, public square, city square, urban square, or ''piazza'') is an open public space, commonly found in the heart of a traditional town but not necessarily a true geometric square, used for community gatherings. ...

at Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

, indicated by a part of the Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

of Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

's Church of St Paul visible behind ''Tom King's Coffee House

Tom King's Coffee House (later known as Moll King's Coffee House) was a notorious establishment in Covent Garden, London in the mid-18th century. Open from the time the taverns shut until dawn, it was ostensibly a coffee house, but in reality se ...

'', a notorious venue celebrated in pamphlets of the time. Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel '' Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

mentions the coffee house in both ''The Covent Garden Tragedy

''The Covent-Garden Tragedy'' is a play by Henry Fielding that first appeared on 1 June 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane alongside ''The Old Debauchees''. It is about a love triangle in a brothel involving two prostitutes. While they are po ...

'' and ''Pasquin''. At the time Hogarth produced this picture, the coffee house was being run by Tom's widow, Moll King, but its reputation had not diminished. Moll opened the doors once those of the taverns had shut, allowing the revellers to continue enjoying themselves from midnight until dawn.Uglow pp.303–305 The mansion with columned portico visible in the centre of the picture, No. 43 King Street, is attributed to architect Thomas Archer

Thomas Archer (1668–1743) was an English Baroque architect, whose work is somewhat overshadowed by that of his

contemporaries Sir John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor. His buildings are important as the only ones by an English Baroque architec ...

(later 1st Baron Archer) and occupied by him at the date of Hogarth's works. It was situated on the north side of the piazza, while the coffee house was on the south side, as depicted in Hogarth's original painting. In the picture, it is early morning and some revellers are ending their evening: a fight has broken out in the coffee house and, in the melée, a wig flies out of the door. Meanwhile, stallholders set out their fruit and vegetables for the day's market. Two children who should be making their way to school have stopped, entranced by the activity of the market, in a direct reference to Swift's ''A Description of the Morning'' in which children "lag with satchels in their hands". Above the clock is Father Time

Father Time is a personification of time. In recent centuries he is usually depicted as an elderly bearded man, sometimes with wings, dressed in a robe and carrying a scythe and an hourglass or other timekeeping device.

As an image, "Father ...

and below it the inscription ''Sic transit gloria mundi

''Sic transit gloria mundi'' is a Latin phrase that means "Thus passes the glory of the world."

Origin

The phrase was used in the ritual of papal coronation ceremonies between 1409 (when it was used at the coronation of Alexander V) and 1963. A ...

''. The smoke rising from the chimney of the coffee house connects these portents to the scene below.

Hogarth replicates all the features of the pastoral scene in an urban landscape. The shepherds and shepherdesses become the beggars and prostitutes, the sun overhead is replaced by the clock on the church, the snow-capped mountains become the snowy rooftops. Even the setting of Covent Garden with piles of fruit and vegetables echoes the country scene. In the centre of the picture the icy goddess of the dawn in the form of the prim

Prim may refer to:

People

* Prim (given name)

* Prim (surname)

Places

* Prim, Virginia, unincorporated community in King George County

*Dolní Přím, village in the Czech Republic; as Nieder Prim (Lower Prim) site of the Battle of Königgrätz

...

churchgoer is followed by her shivering red-nosed pageboy, mirroring Hesperus

In Greek mythology, Hesperus (; grc, Ἕσπερος, Hésperos) is the Evening Star, the planet Venus in the evening. He is one of the ''Astra Planeta''. A son of the dawn goddess Eos (Roman Aurora), he is the half-brother of her other son, Pho ...

, the dawn bearer. The woman is the only one who seems unaffected by the cold, suggesting it may be her element. Although outwardly shocked, the dress of the woman, which is too fashionable for a woman of her age and in the painting is shown to be a striking acid yellow, may suggest she has other thoughts on her mind. She is commonly described as a spinster, and considered to be a hypocrite

Hypocrisy is the practice of engaging in the same behavior or activity for which one criticizes another or the practice of claiming to have moral standards or beliefs to which one's own behavior does not conform. In moral psychology, it is the ...

, ostentatiously attending church and carrying a fashionable ermine muff while displaying no charity

Charity may refer to:

Giving

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sharing

* Ch ...

to her freezing footboy or the half-seen beggar before her. The figure of the spinster is said to be based on a relative of Hogarth, who, recognising herself in the picture, cut him out of her will. Fielding later used the woman as the model for his character of Bridget Allworthy in '' Tom Jones''.

A trail of peculiar footprints shows the path trodden by the woman on her

A trail of peculiar footprints shows the path trodden by the woman on her pattens

Pattens are protective overshoes that were worn in Europe from the Middle Ages until the early 20th century. Pattens were worn outdoors over a normal shoe, had a wooden or later wood and metal sole, and were held in place by leather or cloth ba ...

to avoid putting her good shoes in the snow and filth of the street. A small object hangs at her side, interpreted variously as a nutcracker or a pair of scissors in the form of a skeleton or a miniature portrait, hinting, perhaps, at a romantic disappointment. Although clearly a portrait in the painting, the object is indistinct in the prints from the engraving. Other parts of the scene are clearer in the print, however: in the background, a quack is selling his cureall medicine, and while in the painting the advertising board is little more than a transparent outline, in the print, Dr. Rock's name can be discerned inscribed on the board below the royal crest which suggests his medicine is produced by royal appointment. The salesman may be Rock himself. Hogarth's opinion of Rock is made clear in the penultimate plate of ''A Harlot's Progress

''A Harlot's Progress'' (also known as ''The Harlot's Progress'') is a series of six paintings (1731, now destroyed) and engravings (1732) by the English artist William Hogarth. The series shows the story of a young woman, M. (Moll or Mary) H ...

'' where he is seen arguing over treatments with Dr Misaubin while Moll Hackabout dies unattended in the corner.

Hogarth revisited ''Morning'' in his bidding ticket, '' Battle of the Pictures'', for the auction of his works, held in 1745. In this, his own paintings are pictured being attacked by ranks of Old Master

In art history, "Old Master" (or "old master")Old Masters De ...

s; ''Morning'' is stabbed by a work featuring St. Francis as Hogarth contrasts the false piety of the prudish spinster with the genuine piety of the Catholic saint.

Noon

The scene takes place in Hog Lane, part of the slum district ofSt Giles

Saint Giles (, la, Aegidius, french: Gilles), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 6th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly lege ...

with the church of St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields is the Anglican parish church of the St Giles district of London. It stands within the London Borough of Camden and belongs to the Diocese of London. The church, named for St Giles the Hermit, began as a monastery and ...

in the background. Hogarth would feature St Giles again as the background of ''Gin Lane

''Beer Street'' and ''Gin Lane'' are two prints issued in 1751 by English artist William Hogarth in support of what would become the Gin Act. Designed to be viewed alongside each other, they depict the evils of the consumption of gin as a cont ...

'' and '' First Stage of Cruelty''. The picture shows Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s leaving the French Church in what is now Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develop ...

. The Huguenot refugees had arrived in the 1680s and established themselves as tradesmen and artisans, particularly in the silk trade; and the French Church was their first place of worship. Hogarth contrasts their fussiness and high fashion with the slovenliness of the group on the other side of the road; the rotting corpse of a cat that has been stoned to death lying in the gutter that divides the street is the only thing the two sides have in common. The older members of the congregation wear traditional dress, while the younger members wear the fashions of the day. The children are dressed up as adults: the boy in the foreground struts around in his finery while the boy with his back to the viewer has his hair in a net, bagged up in the "French" style.Cooke and Davenport. Vol.1 ''Noon''

At the far right, a black man fondles the breasts of a woman, distracting her from her work, her pie-dish "tottering like her virtue". Confusion over whether the law permitted slavery in England, and pressure from abolitionists, meant that by the mid-eighteenth century there was a sizeable population of free black Londoners; but the status of this man is not clear. The black man, the girl and bawling boy fill the roles of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

, Venus and Cupid

In classical mythology, Cupid (Latin Cupīdō , meaning "passionate desire") is the god of desire, lust, erotic love, attraction and affection. He is often portrayed as the son of the love goddess Venus (mythology), Venus and the god of war Mar ...

which would have appeared in the pastoral scenes that Hogarth is aping. In front of the couple, a boy has set down his pie to rest, but the plate has broken, spilling the pie onto the ground where it is being rapidly consumed by an urchin. The boy's features are modelled on those of a child in the foreground of Poussin's first version of '' The Abduction of the Sabine Women'' (now held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

), but the boy crying over his lost pie was apparently sketched by Hogarth after he witnessed the scene one day while he was being shaved.

The composition of the scene juxtaposes the prim and proper Huguenot man and his immaculately dressed wife and son with these three, as they form their own "family group" across the other side of the gutter. The head of

The composition of the scene juxtaposes the prim and proper Huguenot man and his immaculately dressed wife and son with these three, as they form their own "family group" across the other side of the gutter. The head of John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

on a platter is the advertisement for the pie shop, proclaiming "Good eating". Below this sign are the embracing couple, extending the metaphor of good eating beyond a mere plate of food, and still further down the street girl greedily scoops up the pie, carrying the theme to the foot of the picture. I. R. F. Gordon sees the vertical line of toppling plates from the top window downwards as a symbol of the disorder on this side of the street. The man reduced to a head on the sign, in what is assumed to be the woman's fantasy, is mirrored by the "Good Woman" pictured on the board behind who has only a body, her nagging head removed to create the man's ideal of a "good woman".Paulson (1979) pp.31–2 In the top window of the "Good Woman", a woman throws a plate with a leg of meat into the street as she argues, providing a stark contrast to the "good" woman pictured on the sign below. Ronald Paulson sees the kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. ...

hanging from the church as part of a trinity of signs; the kite indicating the purpose of the church, ascent into heaven, just as the other signs for "Good Eating" and the "Good Woman" indicate the predilections of those on that side of the street. However, he also notes it as another nod to the pastoral tradition: here instead of soaring above the fields it hangs impotently on the church wall.

The time is unclear. Allan Cunningham states it is half past eleven, and suggests that Hogarth uses the early hour to highlight the debauchery occurring opposite the church, yet the print shows the hands at a time that could equally be half past twelve, and the painting shows a thin golden hand pointing to ten past twelve.

Understanding of Hogarth's intentions with this image is ambiguous, as the two sides of the street, one French the other English, seem equally satirised. In the early nineteenth century, Cooke and Davenport suggested that in this scene Hogarth's sympathies seem to be with the lower classes and more specifically with the English. Although there is disorder on the English side of the street, they suggested, there is an abundance of "good eating" and the characters are rosy-cheeked and well-nourished. Even the street girl can eat her fill. The pinch-faced Huguenots, on the other hand, have their customs and dress treated as mercilessly as any characters in the series. However, this might say more about the rise of English nationalism at the time when Cooke and Davenport were writing than Hogarth's actual intention. Hogarth mocked continental fashions again in '' Marriage à-la-mode'' (1743–1745) and made a more direct attack on the French in ''The Gate of Calais

''The Gate of Calais'' or ''O, the Roast Beef of Old England'' is a 1748 painting by William Hogarth, reproduced as a print from an engraving the next year. Hogarth produced the painting directly after his return from France, where he had been ...

'' which he painted immediately upon returning to England in 1748 after he was arrested as a spy while sketching in Calais.

Evening

Unlike the other three images, ''Evening'' takes place slightly outside the built-up area of the city, with views of rolling hills and wide evening skies. The cow being milked in the background indicates it is around 5 o'clock. While in ''Morning'' winter cold pervades the scene, ''Evening'' is oppressed by the heat of the summer. A pregnant woman and her husband attempt to escape from the claustrophobic city by journeying out to the fashionableSadler's Wells

Sadler's Wells Theatre is a performing arts venue in Clerkenwell, London, England located on Rosebery Avenue next to New River Head. The present-day theatre is the sixth on the site since 1683. It consists of two performance spaces: a 1,500-sea ...

(the stone entrance to Sadler's Wells Theatre

Sadler's Wells Theatre is a performing arts venue in Clerkenwell, London, England located on Rosebery Avenue next to New River Head. The present-day theatre is the sixth on the site since 1683. It consists of two performance spaces: a 1,500-seat ...

is shown to the left). By the time Hogarth produced this series the theatre had lost any vestiges of fashionability and was satirised as having an audience consisting of tradesmen and their pretentious wives. Ned Ward

Ned Ward (1667 – 20 June 1731), also known as Edward Ward, was a satirical writer and publican in the late 17th and early 18th century in London. His most famous work, ''The London Spy'', appeared in 18 monthly instalments from November 1698. ...

described the clientele in 1699 as:

The husband, whose stained hands reveal he is a dye

A dye is a colored substance that chemically bonds to the substrate to which it is being applied. This distinguishes dyes from pigments which do not chemically bind to the material they color. Dye is generally applied in an aqueous solution an ...

r by trade, looks harried as he carries his exhausted youngest daughter. In earlier impressions (and the painting), his hands are blue, to show his occupation, while his wife's face is coloured with red ink. The placement of the cow's horns behind his head represents him as a cuckold

A cuckold is the husband of an adulterous wife; the wife of an adulterous husband is a cuckquean. In biology, a cuckold is a male who unwittingly invests parental effort in juveniles who are not genetically his offspring. A husband who is aw ...

and suggests the children are not his. Behind the couple, their children replay the scene: the father's cane protrudes between the son's legs, doubling as a hobby horse

The term "hobby horse" is used, principally by folklorists, to refer to the costumed characters that feature in some traditional seasonal customs, processions and similar observances around the world. They are particularly associated with May Da ...

, while the daughter is clearly in charge, demanding that he hand over his gingerbread

Gingerbread refers to a broad category of baked goods, typically flavored with ginger, cloves, nutmeg, and cinnamon and sweetened with honey, sugar, or molasses. Gingerbread foods vary, ranging from a moist loaf cake to forms nearly as crisp as ...

. A limited number of proofs missing the girl and artist's signature were printed; Hogarth added the mocking girl to explain the boy's tears.

The heat is made tangible by the flustered appearance of the woman as she fans herself (the fan itself displays a classical scene—perhaps Venus, Adonis

In Greek mythology, Adonis, ; derived from the Canaanite word ''ʼadōn'', meaning "lord". R. S. P. Beekes, ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, p. 23. was the mortal lover of the goddess Aphrodite.

One day, Adonis was gored by ...

and Cupid

In classical mythology, Cupid (Latin Cupīdō , meaning "passionate desire") is the god of desire, lust, erotic love, attraction and affection. He is often portrayed as the son of the love goddess Venus (mythology), Venus and the god of war Mar ...

); the sluggish pregnant dog that looks longingly towards the water; and the vigorous vine growing on the side of the tavern. As is often the case in Hogarth's work, the dog's expression reflects that of its master.Paulson (2003) pp.292–293 The family rush home, past the New River and a tavern with a sign showing Sir Hugh Myddleton

Sir Hugh Myddelton (or Middleton), 1st Baronet (1560 – 10 December 1631) was a Welsh clothmaker, entrepreneur, mine-owner, goldsmith, banker and self-taught engineer. The spelling of his name is inconsistently reproduced, but Myddelton appea ...

, who nearly bankrupted himself financing the construction of the river to bring running water into London in 1613 (a wooden pipe lies by the side of the watercourse). Through the open window other refugees from the city can be seen sheltering from the oppressive heat in the bar. While they appear more jolly than the dyer and his family, Hogarth pokes fun at these people escaping to the country for fresh air only to reproduce the smoky air and crowded conditions of the city by huddling in the busy tavern with their pipes.

Night

The final picture in the series, ''Night'', shows disorderly activities under cover of night in theCharing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City; ...

Road, identified by Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur (c. 1580 – 1658) was a French sculptor with the contemporaneous reputation of having trained in Giambologna's Florentine workshop. He assisted Giambologna's foreman, Pietro Tacca, in Paris, in finishing and erecting the equestria ...

's equestrian statue of Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until Execution of Charles I, his execution in 1649. He was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of ...

and the two pubs; this part of the road is now known as Whitehall. In the background the passing cartload of furniture suggests tenants escaping from their landlord in a "moonlight flit". In the painting the moon is full, but in the print it appears as a crescent.

Traditional scholarship has held that the night is 29 May, Oak Apple Day

Restoration Day, more commonly known as Oak Apple Day or Royal Oak Day, was an English, Welsh and Irish public holiday, observed annually on 29 May, to commemorate the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in May 1660. In some parts of England the ...

, a public holiday which celebrated the Restoration of the monarchy (demonstrated by the oak boughs above the barber's sign and on some of the subjects' hats, which recall the royal oak tree in which Charles II hid after losing the Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 in and around the city of Worcester, England and was the last major battle of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Parliamentarian army of around 28,000 under Oliver Cromwell def ...

in 1651). Alternatively, Sean Shesgreen has suggested that the date is 3 September, commemorating the battle of Worcester itself, a dating that preserves the seasonal progression from winter to spring to summer to autumn.

Charing Cross was a central staging post for coaches, but the congested narrow road was a frequent scene of accidents; here, a bonfire has caused the Salisbury Flying Coach to overturn. Festive bonfires were usual but risky: a house fire lights the sky in the distance. A link-boy

A link-boy (or link boy or linkboy) was a boy who carried a flaming torch to light the way for pedestrians at night. Linkboys were common in London in the days before the introduction of gas lighting in the early to mid 19th century. The linkb ...

blows on the flame of his torch, street-urchins are playing with the fire, and one of their fireworks is falling in at the coach window.

On one side of the road is a barber surgeon

The barber surgeon, one of the most common European medical practitioners of the Middle Ages, was generally charged with caring for soldiers during and after battle. In this era, surgery was seldom conducted by physicians, but instead by barbers ...

whose sign advertises ''Shaving, bleeding, and teeth drawn with a touch. Ecce signum!'' Inside the shop, the barber, who may be drunk, haphazardly shaves a customer, holding his nose like that of a pig, while spots of blood darken the cloth under his chin. The surgeons and barbers had been a single profession since 1540 and would not finally separate until 1745, when the surgeons broke away to form the Company of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgery, surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wa ...

. Bowls on the windowsill contain blood from the day's patients.

Underneath the windowshelf, a homeless family have made a bed for themselves: vagrancy was a criminal offence.

In the foreground, a drunken freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, identified by his apron and set square

A set square or triangle (American English) is an object used in engineering and technical drawing, with the aim of providing a straightedge at a right angle or other particular planar angle to a baseline.

The simplest form of set square is a ...

medallion as the Worshipful Master

In Craft Freemasonry, sometimes known as Blue Lodge Freemasonry, every Masonic lodge elects or appoints Masonic lodge officers to execute the necessary functions of the lodge's life and work. The precise list of such offices may vary between the ...

of a lodge

Lodge is originally a term for a relatively small building, often associated with a larger one.

Lodge or The Lodge may refer to:

Buildings and structures Specific

* The Lodge (Australia), the official Canberra residence of the Prime Ministe ...

, is being helped home by his Tyler Tyler may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Tyler (name), an English name; with lists of people with the surname or given name

* Tyler, the Creator (born 1991), American rap artist and producer

* John Tyler, 10th president of the United ...

, as the contents of a chamber pot

A chamber pot is a portable toilet, meant for nocturnal use in the bedroom. It was common in many cultures before the advent of indoor plumbing and flushing toilets.

Names and etymology

"Chamber" is an older term for bedroom. The chamber pot ...

are emptied onto his head from a window. In some states of the print, a woman standing back from the window looks down on him, suggesting that his soaking is not accidental. The freemason is traditionally identified as Sir Thomas de Veil

Sir Thomas de Veil (21 November 1684 – 7 October 1746), also known as deVeil, was Bow Street's first magistrate; he was known for having enforced the Gin Act in 1736, and, with Sir John Gonson, Henry Fielding, and John Fielding, was responsi ...

, who was a member of Hogarth's first Lodge, Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel '' Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

's predecessor as the Bow Street

Bow Street is a thoroughfare in Covent Garden, Westminster, London. It connects Long Acre, Russell Street and Wellington Street, and is part of a route from St Giles to Waterloo Bridge.

The street was developed in 1633 by Francis Russell, 4 ...

magistrate, and the model for Fielding's character Justice Squeezum in '' The Coffee-House Politician'' (1730). He was unpopular for his stiff sentencing of gin-sellers, which was deemed to be hypocritical as he was known to be an enthusiastic drinker. He is supported by his Tyler, a servant equipped with sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

and candle-snuffer, who may be Brother Montgomerie, the Grand Tyler.

All around are pubs and brothels. The ''Earl of Cardigan'' tavern is on one side of the street, and opposite is the ''Rummer'', whose sign shows a rummer (a short wide-brimmed glass) with a bunch of grapes on the pole. Masonic lodges met in both taverns during the 1730s, and the Lodge at the ''Rummer and Grapes'' in nearby Channel Row was the smartest of the four founders of the Grand Lodge. The publican is adulterating a hogshead

A hogshead (abbreviated "hhd", plural "hhds") is a large cask of liquid (or, less often, of a food commodity). More specifically, it refers to a specified volume, measured in either imperial or US customary measures, primarily applied to alcoho ...

of wine, a practice recalled in the poetry of Matthew Prior

Matthew Prior (21 July 1664 – 18 September 1721) was an English poet and diplomat. He is also known as a contributor to '' The Examiner''.

Early life

Prior was probably born in Middlesex. He was the son of a Nonconformist joiner at Wimborne ...

who lived with his uncle Samuel Prior, the Landlord successively of both the ''Rummer and Grapes'' and the ''Rummer''.

My uncle, rest his soul, when living,On either side of the street are signs for ''The Bagnio'' and ''The New Bagnio''. Ostensibly a

Might have contriv'd me ways of thriving;

Taught me with cider to replenish

My vats, or ebbing tide of Rhenish.

Turkish bath

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited ...

, bagnio

Bagnio is a loan word into several languages (from it, bagno). In English, French, and so on, it has developed varying meanings: typically a brothel, bath-house, or prison for slaves.

In reference to the Ottoman Empire

The origin of this sense ...

had come to mean a disorderly house.

The 6th Earl of Salisbury

Earl of Salisbury is a title that has been created several times in English and British history. It has a complex history, and is now a subsidiary title to the marquessate of Salisbury.

Background

The title was first created for Patrick de S ...

scandalised society by driving and upsetting a stagecoach. John Ireland suggests that the overturned "Salisbury Flying Coach" below the "Earl of Cardigan" sign was a gentle mockery of the Grand Master 4th Earl of Cardigan, George Brudenell, later Duke of Montagu

The title of Duke of Montagu has been created twice, firstly for the Montagu family of Boughton, Northamptonshire, and secondly for the Brudenell family, Earls of Cardigan. It was first created in the Peerage of England in 1705 for Ralph Mo ...

, who was also renowned for his reckless carriage driving; and it also mirrors the ending of Gay's ''Trivia'' in which the coach is overturned and wrecked at night.

Reception

''Four Times of the Day'' was the first series of prints that Hogarth had issued since the success of the ''Harlot'' and ''Rake'' (and would be the only set he would issue until ''Marriage à-la-mode'' in 1745), so it was eagerly anticipated. On hearing of its imminent issue,George Faulkner

George Faulkner (c. 1703 – 30 August 1775) was one of the most important Irish publishers and booksellers. He forged a publishing relationship with Jonathan Swift and parlayed that fame into an extensive trade. He was also deeply involved with ...

wrote from Dublin that he would take 50 sets. The series lacks the moral lessons that are found in the earlier series and revisited in ''Marriage à-la-mode'', and its lack of teeth meant it failed to achieve the same success, though it has found an enduring niche as a snapshot of the society of Hogarth's time. At the auction of 1745, the paintings of ''Four Times of the Day'' raised more than those of the ''Rake''; and ''Night'', which is generally regarded as the worst of the series, fetched the highest single total. Cunningham commented sarcastically: "Such was the reward then, to which the patrons of genius thought these works entitled". While Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole (), 4th Earl of Orford (24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English writer, art historian, man of letters, antiquarian, and Whigs (British political party), Whig politician.

He had Strawb ...

praised the accompanying print, ''Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn'', as being the finest of Hogarth's works, he had little to say of ''Four Times of the Day'' other than that it did not find itself wanting in comparison with Hogarth's other works.

''Morning'' and ''Night'' are now in the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

Bearsted Collection at Upton House, Warwickshire

Upton House is a country house in the civil parish of Ratley and Upton, in the English county of Warwickshire, about northwest of Banbury, Oxfordshire. It is in the care of the National Trust.

History

The house was built on the site of the ...

. The collection was assembled by Walter Samuel, 2nd Viscount Bearsted

Colonel Walter Horace Samuel, 2nd Viscount Bearsted (13 March 1882 – 8 November 1948) was an Anglo-Jewish army officer and oilman. Samuel was the son of Marcus Samuel, the founder of Shell Transport and Trading, and from 1921 to 1946 served ...

and gifted to the Trust, along with the house, in 1948. ''Noon'' and ''Evening'' remain in the Ancaster Collection at Grimsthorpe Castle

Grimsthorpe Castle is a country house in Lincolnshire, England north-west of Bourne on the A151. It lies within a 3,000 acre (12 km2) park of rolling pastures, lakes, and woodland landscaped by Capability Brown. While Grimsthorpe is not ...

, Lincolnshire.

Notes

a. Ireland and Paulson both put the clock at 6.55 am, though the original painting shows 7.05 am. The difference is due to the reversal of the image. In 1708, E. Hatton recorded the inscription below the clock as ''Ex hoc Momento pendat Eternitas'' in his ''New View of London'' and did not mention a figure above it. The date 1715 is shown on the clock-case in the 1717 volume of ''Vitruvius Britannicus'', so perhaps indicates the clock had been replaced and the inscription changed to ''Sic transit gloria mundi'' as shown here. b. ''Battle of the Paintings'' is Hogarth's take on Swift's ''The Battle of the Books

"The Battle of the Books" is the name of a short satire written by Jonathan Swift and published as part of the prolegomena to his '' A Tale of a Tub'' in 1704. It depicts a literal battle between books in the King's Library (housed in St James's ...

''.Paulson (1992) p.292

c. Hogarth's works indicate that cats were not common pets in London during his lifetime. They are often depicted suffering the consequences of the life of a vagabond on the streets, in contrast to dogs which are normally shown reflecting the feelings of their masters or good-naturedly testing the limits of society (one notable exception is the first plate of ''The Four Stages of Cruelty'' in which the cruelty of society is reflected by the torture of the faithful dog).

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

''Morning''

at National Trust Collections

''Night''

at National Trust Collections

"William Hogarth - Four Times of the Day", La Clé des Langues (English)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Four Times Of The Day 1736 paintings Painting series Paintings by William Hogarth Paintings in the West Midlands Paintings in the East Midlands